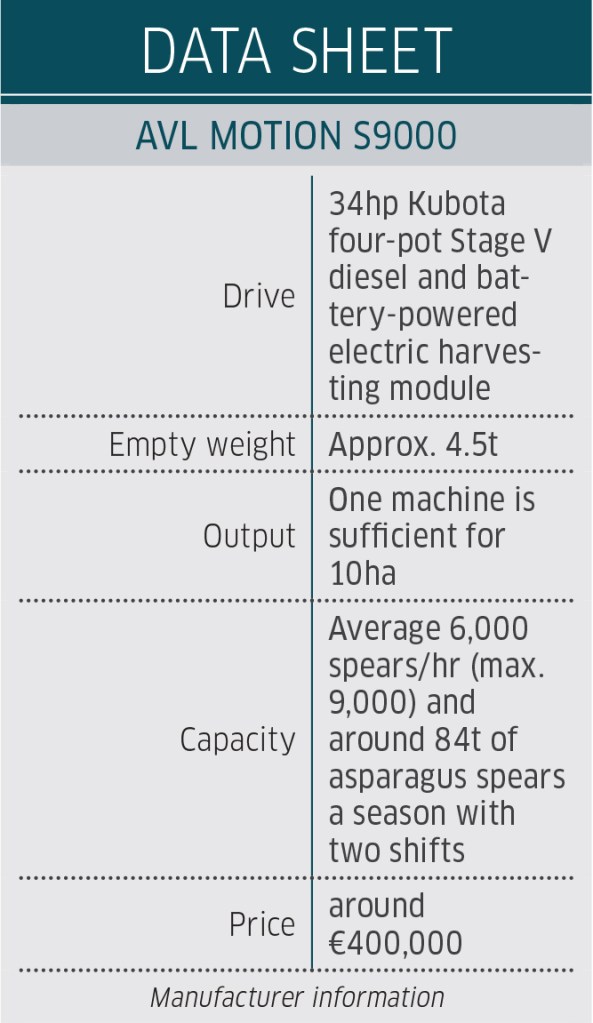

The S9000 automatic white asparagus robot replaces as many as a dozen pairs of hands; slashing labour harvesting costs by up to 80%. The diesel-electric vehicle is made by Dutch firm AVL Motion.

KEEPING IT BRIEF

- When white, green and purple are lumped together, approx. 192,000ha of asparagus is grown globally. China is the world’s largest producer (59,200ha), followed closely by Europe (58,000ha) and North America (42,000ha).

- White asparagus, or white gold as it is often referred, is the most popular colour, accounting for 33,779ha of European production. Germany has the largest area (17,640ha), followed in second place by France (4,200ha) and the Netherlands in third spot (2,970ha).

White asparagus is a totally different ball game to the other two colours, green and purple, which are harvested above ground. White spears are harvested entirely underground just as the tips start to break through the surface of the bed. It is all about timing and the window of opportunity to harvest a spear at the right length and quality is narrow. The trick to ensuring that spears remain white is to cover with rows with a layer of plastic.

Removed for a few seconds to expose the tops of the beds, spear cutting is traditionally done manually using an asparagus knife. Harvested from early-April to mid-June, the process requires a lot of seasonal labour and thousands of workers (mostly migrants) trawl through the asparagus fields for the hectic two-to-three-month season.

Labour is not only scarce, but also costly. For example, a couple of years back, the minimum hourly wage in Germany was €8.00/hr. This now stands at nearly €13 for the same hour and from 2026 will rise again to €16/hr.

“It will soon be no longer feasible to harvest the crop by hand,” says AVL Motion CEO, Sander Wientjes.

Machine thinking

There are numerous mechanical aids to remove the plastic from the beds, and there are also machines to harvest the complete bed, albeit non-selectively. The S9000 developed by AVL Motion is the only machine that automatically and selectively harvests the spears.

To do this it uses a combination of cameras, laser sensors and AI. The cameras are equipped with smart software to quickly locate the tip of an asparagus spear.

The coordinates are relayed to one of the 12 rotating robot harvest modules. This is the bit we were unable to see, but once it is positioned above the spear, it sinks into the ground, cuts through the asparagus at its base (length is programmable from 25-40cm), plucks it from the bed and places it on a conveyor belt.

From here, they steady flow of spears are elevated to the operating platform from where they are put in crates. This is one of the few manual jobs for the operator. Another is to offload the spears at the headland, ensure that the plastic film does not twist as it is laid back on the bed, and turn the machine at the end of a run.

Headland turning is done using a hand-held remote control. Before entering the next row, the operator pulls back a length of the plastic. Then, with the machine in position, the film is fed into the front of the harvester. From then on it travels automatically through the machine and is deposited back down on top of the bed. The operator then secures it and rejoins the harvester.

Capable of working on the standard bed widths of 1.7 or 1.8m, the S9000 can theoretically work 24/7, but this would create challenges in terms of logistics, sorting and grading. For example, cut spears need to graded and cooled within a couple of hours, and designing a system to collect spears from the field in the middle of the night will not be an option for most growers.

Rapid growth

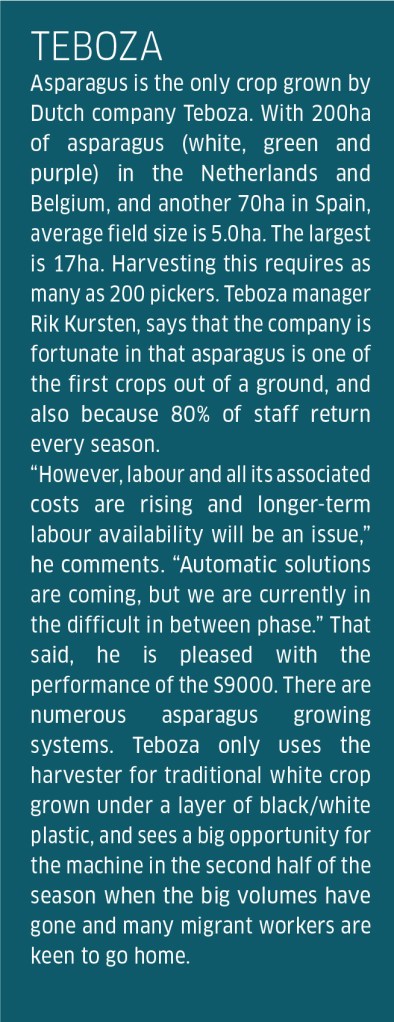

Spears can grow upwards at speeds of 0.75cm/hour and are generally harvested every second day. The Teboza machine forms part of a research project for Wageningen University Research (WUR). This reduced the number of working hours to around 10 a day in the 5.0ha field (2.5ha each day).

However, the other three pre-production machines work two eight-hour shifts from 6am to 2pm and 2pm to 10pm. This allows the harvester to take care of 10ha (5.0ha one day and the other 5.0ha the next). Machines generally average around 1,000 hours a season. Working two shifts, one machine can harvest upwards of 84t of spears.

A hand picker cuts an average of approx. 300 spears an hour. It depends on the crop and field length, but the S9000 is said to be easily capable of averaging 6,000 spears in the same hour, and a maximum of 9,000 (hence the model number); roughly the same output as 30 hand pickers. “We started with 4,200 spears an hour,” comments the CEO, “but have gradually tweaked the system and improved the software.”

The future

The initial focus is with the two main European markets of Germany and the Netherlands, but Mr Wientjes reckons that the global potential for the S9000 is huge. He is confident of finding homes for up to 150 of the €400,000-costing machines by 2028. Based on the available area, the maximum potential of machines are 725 units, and AVL Motion aims to have annual sales of 300 by 2030.

“This is a realistic goal,” he comments. “Many growers have had enough of the difficulties of obtaining hand labour and managing people and are looking for automatic harvesting solutions. Also, labour costs are rising so significantly that growers do not have a feasible business model.”

From an engineering aspect, the machine is ready, but we can expect to see further tweaks to the dashboard to provide growers with additional monitoring information. The machine generates a lot of data and AVL would like to display some of this on the terminal.

Something that could be introduced is a transport system to move the machine between fields. Not all growers have a 10ha field of asparagus where it can be left all season. AVL Motion continues to puzzle the options.

Steven Vale

For more up-to-date farming news click here and subscribe now to profi and save.