Unmanned aerial vehicles – drones – have become part of the armoury for making agronomic decisions but are also now showing the potential to compete with existing applications equipment.

The ability of an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) to access locations that can’t easily be reached on foot or in a vehicle, offers huge potential on agricultural and horticultural land, as well as in forestry and moorland settings.

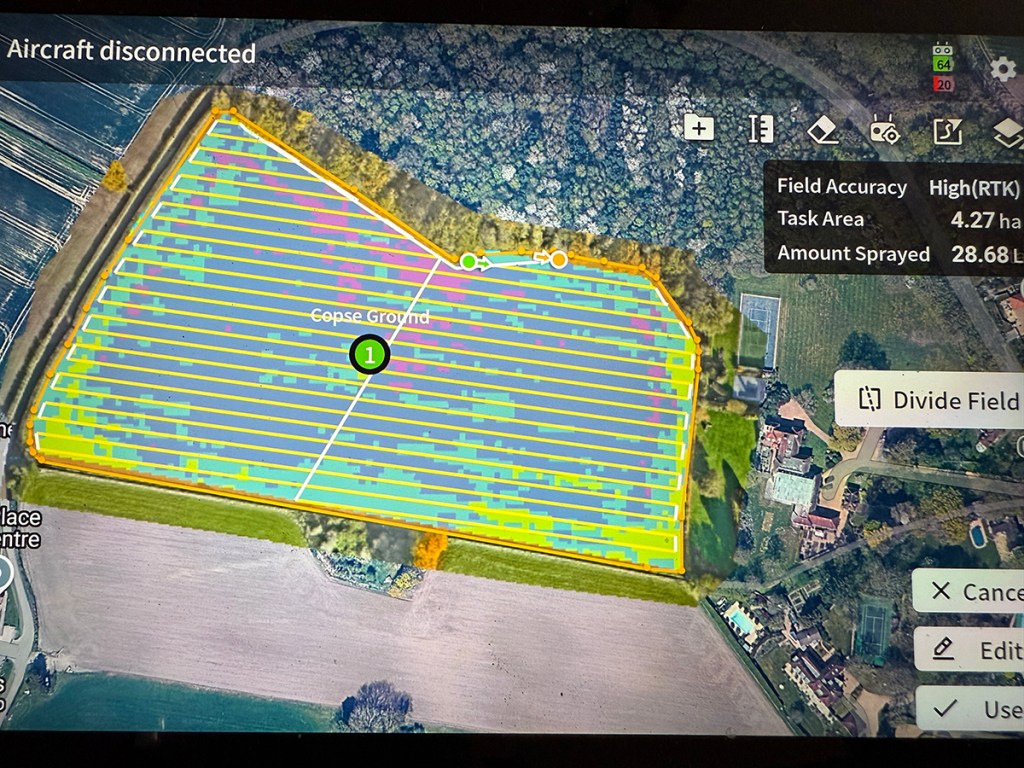

Many farmers and their agronomy suppliers are already using drone technologies to more accurately study and map land and crops for greater precision, and now interest is growing in deploying unmanned aerial systems (UAS) to apply plant protection products.

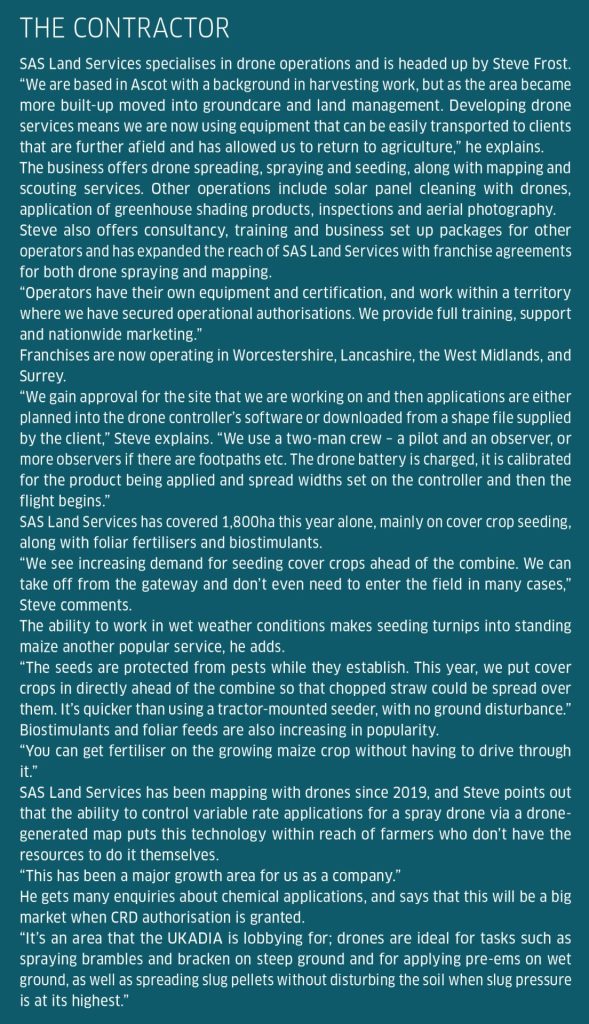

Visibility and utilisation of drones in farming has expanded significantly since the launch of DJI drone supplier and Skippy Scout software developer Drone Ag in 2015, comments chief operations officer, Alex Macdonald-Smith.

“As with all novel technologies, drones were initially considered to be fringe to mainstream agriculture. But the interest in sustainability, improving soil health and reducing disturbance to the environment has increased the opportunities for their use for applications.

“Technology has also advanced, and costs have come down in that time, and there are a number of manufacturers in the market. DJI has gained ground and become the largest drone manufacturer in the world with a >70% market share and massive R & D budget, but also due to the easy adoption of the machines and continues to develop cutting edge solutions for agriculture that are easy to learn.

Many farmers are already familiar with drones for the collection of data.”

Alex comments, however, that although agricultural drones have been in existence since the 1980’s, until this year there has been no organised collaboration in the UK between industry stakeholders, and thus no joined-up route to influencing legislation or the direction of the sector.

“The UK Agricultural Drone Industry Association was founded in July, aiming to offer a voice for the industry,” he explains. “It will bring together professional drone pilots, commercial operators, researchers, agronomists and developers plus training providers and will represent safe, professional and recognised operations in agriculture.”

One goal is to focus on Plant Protection Product access, spraying approval and CRD, HSE and CAA collaboration.

Choose your weapon

Drones come in all shapes and sizes, but generally a ‘spray drone’ – a UAV that is capable of carrying and applying products – is a different machine to that used for data collection.

“The DJI Agras T50, for example, can be used for limited remote sensing, but is not suitable for scouting or mapping at scale,” explains Alex. “It has a 50kg payload and is designed for applications.”

Sheer size is the first feature of a spray drone to strike those unfamiliar with the machines – the DJI Agras T50 measures 2.8m x 3.0m with the arms and propellers unfolded. A dual atomising system has a 40-litre spray tank and nozzles spaced at 1.57m, designed to offer a spray width of 4.0m to 11m at 3.0m above the crop. Flow rates are up to 16l/min with two nozzles or 24 litres/min with four. Alternatively, a spreading system can apply granules from 0.5-5.0mm from a 75-litre tank to width of 8.0m. Multiple radar systems and visual sensors offer obstacle avoidance.

DJI is set to launch an even larger applications machine to the European market at Agritechnica, the Agras T100, which will have a payload of 100kg, 100-litre spray tank and 40l/min flow rate.

Flight times differ too – the T50 can fly for nine minutes on a battery charge, optimised for applications use, whereas the larger areas to be covered for scouting are catered for by 40-45 minute flight time on a small camera drone, explains Jonathan Trotter, technology trial manager at Agrii, which is undertaking extensive research on the use of drones for agronomy and application purposes.

Legislation

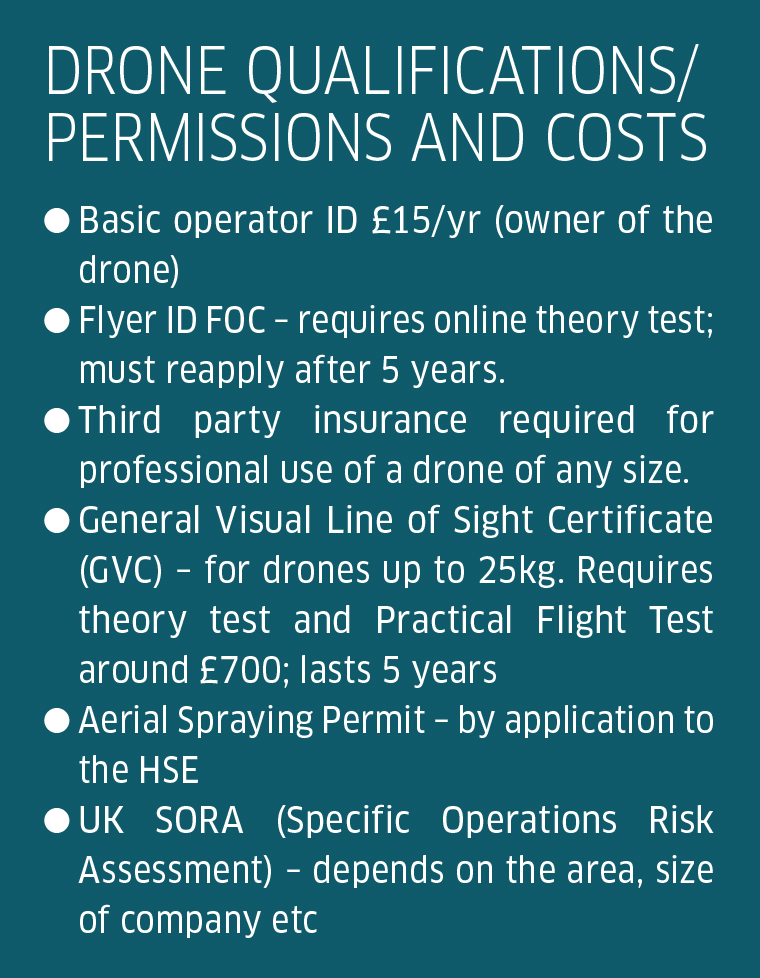

Registration with the Civil Aviation Authority is required to operate (ie to own and/or be responsible for) any drone either with a camera or over 250g in weight, and spray drones require different and much more extensive permissions compared to off-the-shelf camera drones, Jonathan points out.

“The current complexity of applying for permission for a spray drone means that using this sort of technology on farm will likely be more a job for a contractor than for individual farmers. A pilot will need specific qualifications on top of the standard Flyer ID and Operator ID. They’ll also need the General Visual Line of Sight Certificate (GVC) and a Specific Operations Risk Assessment (UK SORA) from the CAA to even take off from the ground,” he says.

Applications generally require consultancy assistance, so it is not a cheap process, and Alex comments that an extension of the Predefined Risk Assessment (PDRA) is on the lobbying list for UKADIA.

“It would undoubtedly increase the adoption of the technology on farm.”

Jonathan also highlights the lengthy nature of the process: “Agrii’s application runs to 300 pages of risk assessments and operating procedures. If you already have drone experience and a GVC it can take six to eight months to get the application built, submitted and approved,” explains Alex. “Expect to pay anything between £2,000 and £13,000 for approval for a large drone, depending on the size of the enterprise.”

Advice to farmers considering using drone services is centred on checking and ensuring that operators have the right authorisations and are not applying products that they shouldn’t.

What can the drone apply?

Currently, products that are not permitted in the UK are those with a MAPP number, ie authorised pesticide products, Jonathan explains. “Essentially any product that is spreadable can be applied with a drone – a range of fertilisers, seeds, pod sealants and biologicals have all been successfully applied. We have carried out a trial of wildflower seeding to see how effective the drone is at spreading the seeds.”

Drone Ag has trialled seeding buckwheat and oilseed rape into a growing crop of wheat.

“We’re studying the cost of establishment compared to traditional methods. By broadcasting seed into a standing crop, it is covered by chaff when the crop is combined, retaining moisture and encouraging the seed to chit,” explains Alex.

Output is a consideration – DJI claims 21ha/hour for the T50, but when broadcasting seed, 6.0m bout widths are used, and he suggests that 10ha/hr is more realistic.

“Outputs for spray operations could be higher, but that depends on the protocols introduced by the CRD to reduce drift risk.”

However, he points out that the forthcoming 100kg capacity T100 could potentially double operational efficiency.

Other useful applications could include slug pellets, and pod sealants alongside glyphosate on OSR at desiccation timing.

Away from broadacre agronomy, further opportunities include solar panel cleaning and spraying for crops or invasive plants that grow on hillsides, gaining coverage in a vertical rather than horizontal plane. Software in development for tree recognition could also enhance use in silviculture.

Practicalities

Another barrier to overcome is to gain CAA approval to fly multiple drones from a single point, which they are technologically designed to do.

“Used in pairs from the same controller, the T50 has the potential to match the output of a self-propelled sprayer; the system is designed to handle up to three, which would exceed it and cost considerably less to purchase.”

Jonathan comments that using more than one drone currently requires more manpower than traditional applications in order to meet safety requirements; to attain the same output as a self-propelled sprayer you’d need a well-briefed three- to four-person ground team.

Flying Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) with the drone requires special permission from the CAA and a high level of risk mitigation, Alex points out, it is especially relevant for upland areas where it can be difficult to maintain line of sight.

Extended Visual Line of Sight (EVLOS) operations currently require the use of an observer in the field who can communicate with the ground control station at a remote location and could be useful in the future. Separation Distance is a further consideration, designed to protect ‘uninvolved people’ from drone activities, such as adjacent to road and footpaths.

“It may be necessary to avoid applications to headlands that border these areas of increased risk, which could have agronomic implications.”

Agronomist opportunities

Agrii has 22 agronomists who are also drone operators, working closely with Drone Ag on the development of Skippy Scout to explore its potential for decision management and informing applications.

“We see it as an area of growth and one that will be integrated with our agronomic services going forward. We are currently evaluating new services such as the use of crop-specific Green Area Identification data collected via the drone in combination with remote sensing via RHIZA and soil mineral nitrogen results. There’s no reason that a nitrogen application derived from this data couldn’t then be applied via drone as well.”

Contract drone spraying is another future possibility for Agrii, which already has a fleet of 27 self-propelled sprayers, operating mainly in Scotland.

“There’s still a lot of work to be done to see what the drone is capable of, and we certainly see ourselves being a in a good position to support growers and contractors using the technology, should we determine a market for it and benefits for our growers.”

The moorland opportunity

Drones have potential for effective bracken control on moorlands.

“Bracken poisons drinking water and pollutes air wth spores, while outcompeting pollinator-supporting heathers and wild grasses. It threatens habitats and is poisonous to livestock, while also harbouring ticks, which can cause Lyme disease, and we’re highly concerned that the pressure it is putting on our ecosystems and economy is far worse than originally recognised,” Alex explains.

Approval for Asulox, the main herbicide used to control bracken, has now been revoked for helicopter application and it can’t be effectively controlled by cutting or burning alone.

“Drones could be an efficient way to spray off thick, monoculture bracken – which spreads by 3-5% of its surface area each year – with glyphosate,” he adds.

Trials have shown that controlled burning of bracken, followed by spraying, before broadcasting beneficial seeds and burning once again to denature the sprayed area are effective; the moor is then overseeded with native species if necessary.

“Notwithstanding the interest for agronomic use, bracken spraying could be the largest potential market for drones, once chemical approval is obtained,” comments Alex.

Jane Carley

For more up-to-date farming news click here and subscribe now to profi and save.