Industrial hemp now forms a useful component within one Gloucestershire farm’s rotation, favoured for its low cost of production that provides a source of renewable fibres for industrial use. In addition to sequestering carbon, the crop has also been found to boost soil aggregation. Could hemp be about to make a comeback?

KEEPING IT BRIEF

- No pesticides required.

- Square bales simplify processing.

- Rain doesn’t spoil the crop.

Three years ago, Guiting Manor Farms introduced hemp to its rotation as the farm looked for ways of reducing exposure to fluctuating commodity prices, while also searching for an additional break crop to oilseed rape. Farms director, Nick Bumford reasoned that hemp’s renewable qualities and tough natural fibres offer a new revenue stream for Guiting Manor Farms, while extending its rotation by one-to-two years when growing oilseed rape.

“We’ve grown oilseed rape since the 1990s, and the yield uplift it brings for subsequent wheat crops is hard to over-look,” he says. “But with flea beetle and seed dressing challenges in recent years, we’ve been looking for an additional crop that could bring financial and agronomic benefits to the business.”

Nick reckons that the early years of hemp production have needed a lot of head-scratching and research, and the farm is still managing its way through growing the crop while looking to validate the entire process.

“It’s early days for us and we’ve only had three years’ experience of growing hemp,” says Nick. “While it needs no special processes to grow, there’s little information out there to draw on. Our local arable groups are watching with interest, as are we.”

He says that the crop does love sunlight, adding that there are better locations where sunlight and warmth are much more readily available than the middle of the Cotswold hills.

“This year’s extremely warm and very dry conditions have been challenging, and as a result of differing soil moisture levels, the yield variation has ranged from 2.5t to 7.0t/ha,” he says. “Our hemp crop has survived on little more than dew and soil moisture, where everything else has died off prematurely. That said, its drought resistance has been remarkable in those areas where the crop started in a moist seedbed.”

Hemp is considered one of the most sustainable and low-input crops farmers can grow. With a seed rate of 50kg/ha and a seed cost of £323-421/ha depending on variety, it is more expensive than cereals. Though its only additional input is a small dose of fertiliser.

Simple start

Guiting Manor Farms’ 2025 crop totalled 46ha and was sown in late April following stubble turnips that had first been ravished by the farm’s breeding ewes. Seedbed preparation amounted to a pass with a 6.0m Horsch Terrano ahead of drilling, with the farm’s 8.0m Väderstad Rapid equipped with System Disc putting in the seed. A dusting of fertiliser and a pass with the Dalbo rolls completed the establishment process.

“That’s it,” he says. “There are no sprays needed or additional fertiliser requirements either. The next time we went into the field was to mow it, at the start of August.”

Industrial hemp’s short growing season – typically 100-120 days – sees the crop reach around 3.0-4.0m in height. With leaves acting as solar panels to convert sunlight into fibres, the plant can grow 25mm/day in hot weather. Every hectare sequesters 6-10 tonnes of carbon/season, both above and below ground.

“Each plant puts down a tap root, and a root mass too – it’s almost a combination of rape and maize root structures,” explains Nick. “We’ve found it to be good at soil-fixing and aggregating – which all helps our thin Cotswold soil structure.”

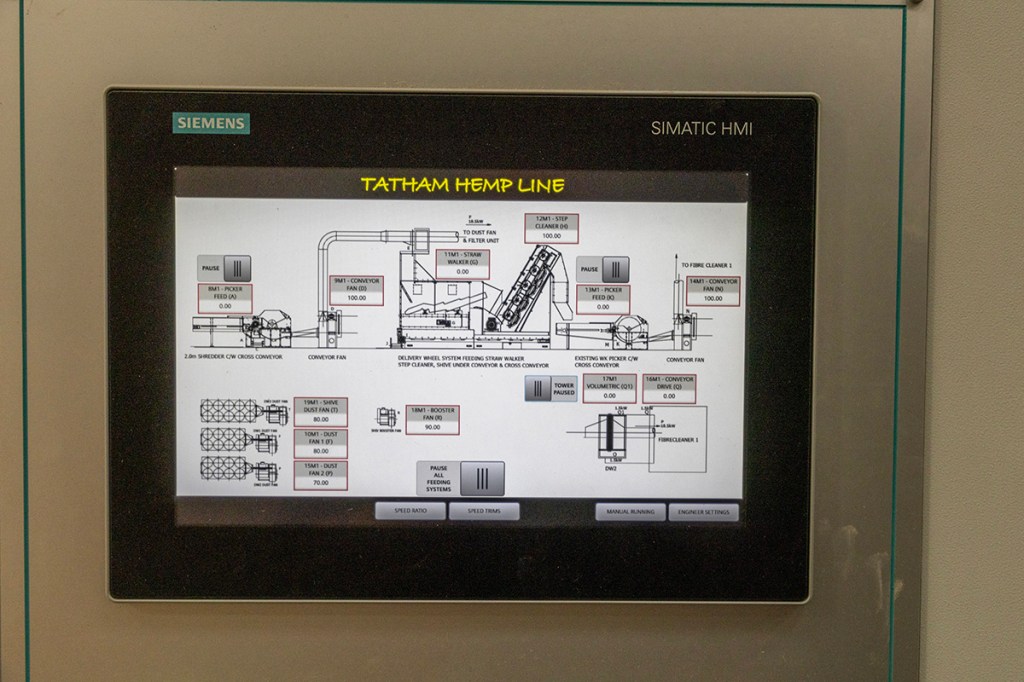

As soon as the crop starts to flower, it has to be cut down, to avoid a switch to high lignin creation which can reduce the quality of fibres sought by the processing plant. The crop doesn’t have to travel far, as the processing plant is based in one of Guiting Manor Farms’ industrial-let buildings (see The role of Fibra).

“By law, we’re not permitted to remove any leaf or flower from the field and we have to confirm that as part of the annual growing declaration,” he says. “We can only remove the stalk for processing, once it has been through an intense period of in-field decomposition – or retting.”

Hemp is part of the Cannabaceae plant family, though it contains less than 0.2% of the psychoactive substance THC (Terathydrocannabinol), compared to over 20% for the mind-altering illegal drug, cannabis.

Laumetris mower

Mowing is not the task of a traditional disc or drum unit. This needs a specialist approach, and processing partner Fibra has the kit to do the job. It’s a Laumetris KP-4 trailed unit that cuts on one side only, chopping down the lofty crop into 60cm stalks to aid with retting – the process of separating those plant fibres.

The KP-4 is hired to growers and uses four reciprocating knife assemblies that extend horizontally up to 2.8m from the machine’s body, and is akin to a modern-day incarnation of Boadicea’s chariot. The horses up front are different though, with Guiting Manor Farms’ Fendt 718 providing the power and stability for the multi-knife machine.

Each knife bar is staggered vertically and horizontally to allow the crop to fall past each knife as it is cut from the top of the plant, downwards. With a forward speed of around 12-18km/hr, the mower slices through the crop like a series of samurai swords, allowing the shortened pieces of hemp to lay on top of the remaining stubble.

“It’s the only bit of specialist kit that’s needed to harvest the crop, and the offset blades are why we can’t plant the crop right up to a field boundary,” adds Nick. “Other than that, we need a rake, a tedder and a square baler – all of which we have, for our own hay and straw requirements across the farm.”

Retting is the process of separating plant fibres, and it needs mother nature’s help to do so. The inner parts of the stem have a wood-like interior, known as the hurd; while the fibrous exterior is known as the bast. Both parts are important and can be utilised. While the bast can be used for items such as clothing, the hurd can be used for paper, hempcrete and insulation, for example.

“As the hemp starts to break down during retting, we rake the crop into swaths to further encourage the process,” he says. “Then we’ll rake again, to move the swaths. Doing so helps to accelerate the retting process, but there’s an element of trial and error with timing and the weather. It’s something we are still learning how to manage.”

The 2025 season saw the mown crop raked into rows around 10 days after being mown. Then a few weeks later, the rows were repositioned using the rake to enable ground beneath the crop to dry while inverting stalks. A further pass was needed with a tedder to encourage yet more breakdown of the stalks, before the crop was finally pulled back into swaths and baled. This took place towards the end of September.

“This was the first year we needed to ted the crop, simply because of the very dry conditions combined with a lack of moisture that is needed to help with retting,” explains Nick. “Our 35-year rainfall average is 855mm, but so far this year we’ve barely passed 260mm. So, we’ve had to work a bit harder at getting the hemp fibres into a condition where they can be easily processed, to help create that saleable product.”

Owned by the Guiting Manor Amenity Trust, the 587ha farm grows a wide arable rotation that includes winter sown wheat, barley and oilseed rape, plus spring barley, industrial hemp, stubble turnips and grass, reaching a 932ha total through tenancy and contract farming agreements. Alongside combinable crops and grass are permanent pasture, woodland and environmental stewardship enterprises, plus 600 breeding ewes with 14 rams producing over 1,000 lambs.

Diversification

The farm has embraced diversification with firewood sales, equine and livestock bedding and forage supplies, industrial-let buildings, industrial hemp processing, pony paddock rental agreements and electricity generation through roof-top mounted arrays totalling 0.4MW.

“We went through a period of farm building modernisation and future-proofing with a speculative view to embracing other industrial uses,” he says. “Andrew Jones of Fibra approached us about setting up a plant on-farm, and also to discuss Guiting Manor Farms being one of his hemp growers. The time was right for trying a green, renewable product.

“As we are finding out, hemp is a crop that slots into our rotation needing very little in the way of inputs, nor does it need big ticket items such as a sprayer, combine or a grain dryer,” he says. “It is a low-pressure crop that demands little from those who grow it, and it can be managed without impacting on traditional summer-time harvest pressures. It doesn’t spoil if it gets rained upon, and it doesn’t need immediate attention, at any time of the growing season, unlike some of the more traditional crops we grow.”

The farm’s Cotswold brash is abrasive, and when it comes to retting and baling hemp, it’s hard on kit.

“There’s not a lot we can do about the stone content of our soils,” he says. “It’s tough on kit, and we’ve had our fair share of punctures with the rake and tedder this year. But we’re not chasing high output as if we were racing to stay ahead of a forager. We can travel slower to be sympathetic on kit and be thorough in what we move, but unlike straw that’s dropped out of the combine, the hemp doesn’t sit high on stubbles awaiting a baler’s pickup reel. The stubble retts down too, so the crop is as good as sat on the soil and stones.”

The farm’s big square baler, a Fendt 1290 six-stringer, packs hemp into 600kg bales compared to 400kg packages with straw and 500kg packages with hay. The extra bale weight is not a result of stones being gathered up, though a fair few of them are captured and removed in the processing plant as each bale is fed into the plant.

“We do need to draw a yearly income from hemp, and we’re currently sat on close to three years’ of hemp bales in the barn as Fibra’s new processing plant and marketing activities gather momentum,” he says. “The plant is not yet operating at full capacity, but when it does, we could expand our growing area.”

“We’re currently happy with the progress made so far. And importantly, we’ve not needed to invest in any extra kit to grow this interesting crop.”

Summary

Given the challenges with growing oilseed rape, industrial hemp certainly has a place on UK farms as an additional break-crop, as experienced by Nick Bumford and his team at Guiting Manor Farms. As a low-input crop with light demands on machinery, the risk for growers stepping into industrial hemp is low, but there is work to be done by Fibra for example, to continue developing markets for the material after it has been processed. Only then will its true potential be realised as a sustainable and renewable break crop that could help reduce a grower’s exposure to fluctuating commodity prices.

Geoff Ashcroft

For more up-to-date farming news click here and subscribe now to profi and save.