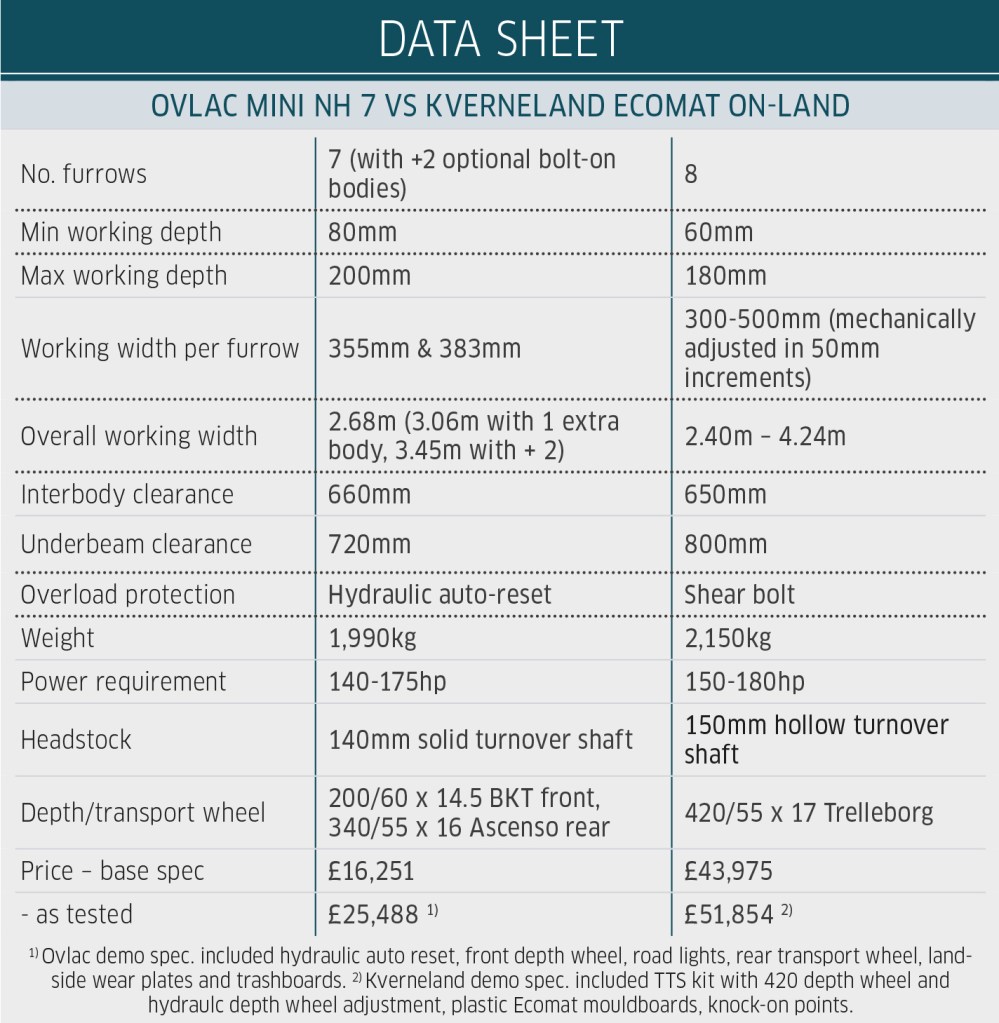

Shallow ploughing might not be everyone’s cup of tea but with increased focus on carbon emissions and the obvious cost advantages of just skimming under the surface, it’s a practice that is receiving renewed attention. We put two of the front-runners in the field side-by-side earlier this year..

KEEPING IT BRIEF

- The Ovlac Mini is available in two to nine furrows.

- Kveneland makes the Ecomat in five to eight furrows.

- As tested the Ovlac is £25,488, the Kverneland £51,854.

While there’s nothing new in the practice of shallow ploughing, it’s a technique that has never really taken a grip as a mainstream cultivation approach. Consequently, manufacturers of these niche inversion tillage tools have come and gone but a few players remain steadfast in the game. French manufacturer Bugnot continues to have a decent following in its home market with its RapidLab skim plough but due to the small numbers shifted this side of the Channel, importer ArbForest doesn’t run a demo machine.

So, that leaves just two others – Ovlac and Kverneland. Last spring we asked each to supply us with their most popular shallow ploughs to assess just how well they work and how easy they are to set up.

From the south

Located in northern Spain, Ovlac has been building ploughs for over 75 years and today claims to be the country’s largest manufacturer of soil-engaging equipment. The firm is regarded as something of a specialist in shallow inversion tillage with a range built specifically for that growing market.

Alongside a full offering of conventional and reversible ploughs from two to nine furrows – mounted and semi-mounted – the company has developed its Mini range to work at depths of between 8cm and 20cm. According to the company, reducing share depth to less than 15cm can half power requirements enabling smaller tractors to cover far greater working widths – it is apparently possible to have a 13-body plough spanning 5.0m on a tractor of just 260hp.

From the north

It’s a similar story with Kverneland which builds the entirety of is plough line-up in Norway. Despite having a short break in production of its shallow plough offering a few years back, the company has recently invested a good chunk its R&D budget in its Ecomat shallow ploughs, widening the range to include smaller in-furrow six-, seven- and eight-body models suitable for more modestly sized tractors.

For now though we’re told it’s the company’s eight-furrow on-land model that attracts most attention and so that’s the demo machine we were given.

Great minds think…

On-land versions prove the most popular for the Spaniards too apparently and consequently it was a seven-furrow Ovlac Mini NH that we received for our in-field comparison.

Albeit very similar on paper, it immediately becomes apparent that these are two very different beasts. Kverneland’s Ecomat On-Land looks much like a standard eight-furrow plough. And that’s because it is.

It’s based on the company’s ever-popular LO-series ploughs and comes with either eight or ten bodies while the smaller in-furrow variants are based on ES-series models and run from five to eight bodies.

In contrast the Ovlac Mini employs a purpose-built multi-beam frame for its five- to 11-body fully mounted models while bigger 12- and 13-furrow versions borrow the single beam design used on the company’s semi-mounted standard ploughs.

Our seven-furrow test model came equipped with a number of options including hydraulic auto-reset and an intriguing-looking front depth wheel.

The eight-body Kverneland landed with shear bolt overload protection and manual vari-width enabling pass-to-pass spans to be adjusted from 2.40m to 4.24m. The seven-furrow Ovlac has two manually set working widths of 2.48m and 2.68m with the ability to add another two bolt-on bodies to take it to a maximum of 3.45m.

In work

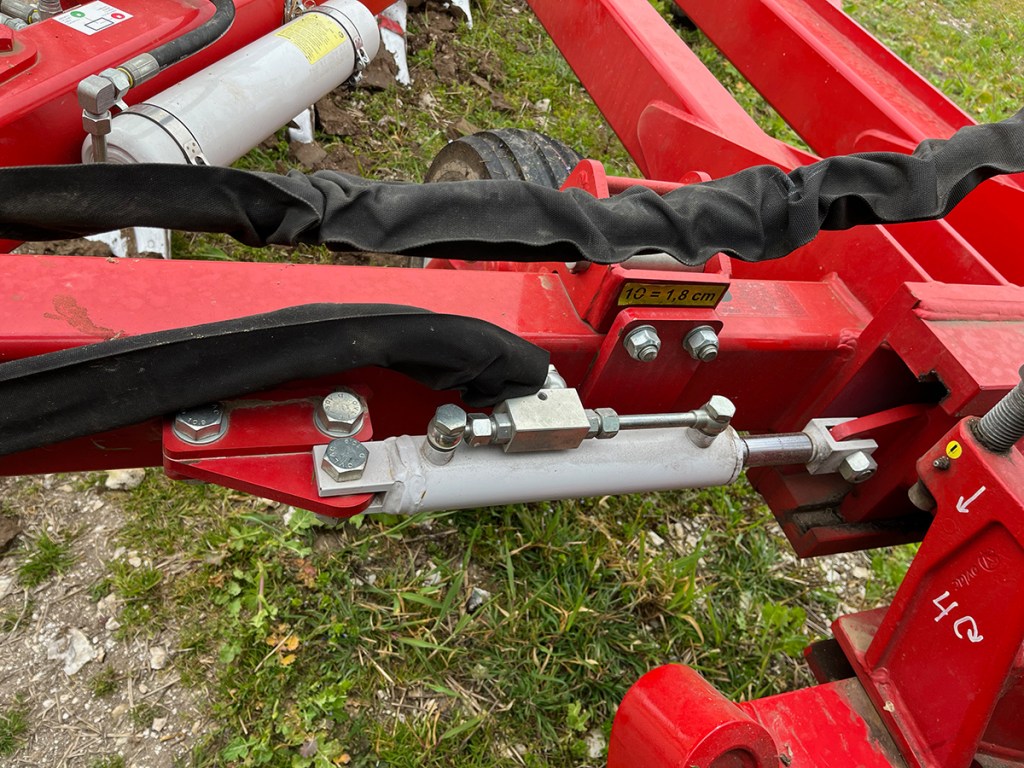

Once pulled into the field, set up with the Kverneland is much like that with a standard plough. A single bolt through the beam in each body bracket varies the angle to alter furrow widths in 5cm increments. Collars on the front furrow width adjustment ram then set the stroke length so that the bean returns to the same angle after each turnover. A large nut on the threaded end of the ram provides fine-tuning.

Adjusting the depth on a standard model is done via a long threaded bar linked to the rear wheel. Our test machine had hydraulic depth control. To tweak it you open two taps, use a spool valve to raise or lower the wheel. Shut the taps and that’s the backend sorted. With a floating top-link it’s just a case of setting the link arms to the right height to get front and rear mouldboards running true.

Body choice

As you’d imagine there’s a whole raft of body choices from the Kverneland parts bin. Plastic and steel mouldboards both come with the same wearing metal as No. 28 bodies and there are the options of carbide tips, knock-on points, quick fit shins, etc…

A landside knife comes as standard to slice through the furrow as it peels off the point. On our test rig we had optional bolt-on trash-boards out in front of each body and there is the option of double fingers running vertically along the top of each board to help flip cantankerous sods over on their backs.

With the job done, it’s time to head for home. The Ecomat’s headstock has a pivoting lower cross-shaft that is locked when in the field. A handle is then flipped with the plough in butterfly position allowing the Kverneland to behave like a semi-mounted rig on the road. With the top link detached, the rear wheel remains fixed while the headstock steers, making the whole setup follow much like a tractor-trailer combination.

It’s fair to say the Ovlac Mini is a simpler beast and consequently setup is more straightforward. First, it’s a case of positioning the sliding headstock in a position where the front furrow is well clear of the rear wheels. This is then easily tweaked on the move from the cab, shifting the whole plough frame left and right accordingly – a useful feature on side slopes where the rig may not track entirely true.

Next up is front furrow depth. With the top-link in the slotted hole, the link-arms are the primary means of regulating how deep the plough works. The optional front depth wheel is there more as a guide – it should only be skimming the surface to ensure there’s still decent weight transfer onto the back of the tractor. That said, it’s a must-have option in our opinion, making the rigid-framed plough much more effective in maintaining a consistent shallow working depth on uneven surfaces.

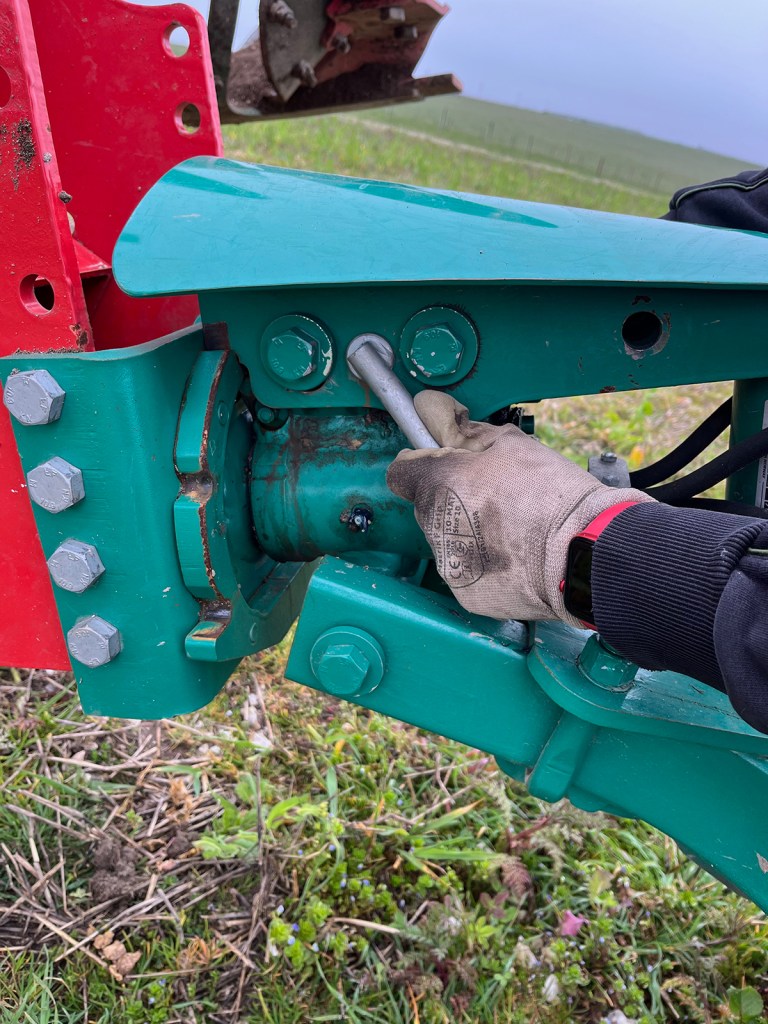

With the front end sorted it’s simply a case of adjusting the turnbuckles on the rear wheel to set the whole frame running true. We can’t overstate how beautifully simple the Ovlac is to set up.

It also has another trick up its sleeve to ensure true tracking behind the tractor. The main headstock cross-shaft can oscillate. This means the plough can find its own line, pivoting around its central pull point and finding the midline between the forces exerted on the landsides and mouldboards. In this way it’s not necessary to make lots of adjustments to ensure the Mini pulls straight. It simply finds its own happy medium.

Again, there is a plethora of body choices for the Spanish plough, steel slatted or solid and plastic for the stickiest conditions. Reversible tips can be bolted on to the front of the flush-fit one-way points which is great for extending the life of wearing metal but creates a step which sticky soil can hang up on. Adjustable landside wear plate extensions are standard as are tweakable trashboards.

For transport the Ovlac has to be hoisted as high as possible to get the rear wheel into its road position. This requires a pin to be removed and positioned in the designated travel hole. Getting the weight off is an awkward finger-snagging process that requires generous doses of right boot. Once tucked under the frame the wheel pivots round corners while supporting the weight of the plough.

Summary

Like other Kverneland ploughs, the Ecomat is often viewed as the gold standard for shallow ploughs. Being arranged around the same basic design as the company’s standard models it has heaps of adjustment in all three dimensions. But that level of sophistication comes with its own inherent complexity. This is no drop it in the ground and go rig. You need to take time to get it set up right to do the best possible job.

In contrast the Ovlac Mini is about as straightforward as it gets. Front and rear wheel adjustments deal with ploughing depth while the sliding headstock sets the front furrow away from the tractor’s rear wheels. The Spaniards’ clever free-floating line-of-pull arrangement means that the plough can never run anything other than true. While this simplicity is great, it does mean there’s less refinement to the Mini and match ploughmen might feel they’re lacking all the tweak-ability they’d like.

The upside of this lack of complexity is that it’s a massively cheaper build. While the eight furrow Kverneland comes in at north of £50k, an equivalent 7+1 Ovlac stands at about £21,000.

DIGGING DEEP INTO SHALLOW PLOUGHING

Being able to bury trash and control weeds while not exerting huge loading on the tractor makes shallow ploughing an attractive proposition on the face of it. But as with anything agricultural it’ll only suit certain sites, soils and systems.

Much research has been done on the subject particularly in northern Europe and Scandinavia. Trials with organic pea and oat crops in Germany compared the effects of 7-10cm and 25-30cm ploughing depths. Unsurprisingly penetration resistance (compaction) was greater in the 14-28cm soil zone under the shallow regime whereas soil loading due to the increased draft requirements with deep ploughing increased compaction and had an impact on yields, reducing them by between 12.1% – 20.8%. Annual weed infestation levels were generally higher in the shallow inversion areas.

The overall finding suggested that shallow ploughing mitigates the risk of a decrease in crop performance as a result of heavy field traffic and its reduced power/labour requirement goes a long way in offsetting the potential increase in weed burdens when compared with deep inversion.

Comprehensive field trials in Norway throughout the mid 2000s looked at the impact of reduced ploughing depth alongside the difference between in-furrow and on-land approaches.

In-furrow ploughing was found to significantly reduce the air-filled pore space and subsequent permeability when soil conditions were sub optimal however it had very little effect when ploughing was performed with favourable moisture levels.

Shallow ploughing led to marked increases in perennial weed biomass and particularly allowed couch grass to flourish. However, reduced depth cultivation was shown to provide greater reserves of plant-available P & K. It is asserted that this is due to the fact that shallow inversion tillage favours the formation of cavities where air and moisture can work together to provide a microclimate to suit the bacteria that can decompose large volumes of crop residue, producing a clay-humic complex that mineralises nutrients and increases the natural fertility of the soil.

A six-year long investigation in the Netherlands set out to ascertain the minimum ploughing depth possible for sustainable weed control and acceptable yields. Working at depths of between 12-20cm depending on conditions, it was found that crop performance was similar with both conventional and shallow approaches but weed populations did increase when working depths reduced to less than 20cm.

The trial also looked at the impact of non-inversion tillage practices for slurry and muck incorporation, finding that ammonia losses leapt from 10% to around 60% when going from the plough to a stubble cultivator.

There is still plenty of debate about the optimum depth of ploughing. Some studies suggest that organic farmers should reduce ploughing depth to a minimum of 8cm. However, in order to bury green manure, annual weeds and crop residues, working depth should be at least 12cm and for control of perennial weeds it should be 20cm or more.

After shallow ploughing the surface tends to be less undulating than after conventional ploughing. This is mainly due to the difference in depth-to-width ratios. Generally shallow furrows run at 2:5 instead of 2:3 with traditional deep inversion. Reduced surface roughness after ploughing can remove the need for a tillage pass for seedbed preparation, making the practice even more financially attractive. But in situations where deep ruts need to be levelled, for example after root crops or maize, shallow ploughing will struggle to alleviate the issues.

If it’s possible to achieve almost complete surface burial working at less than half the depth of a normal plough with an implement that requires half the power, while doing a far better job of inversion than a cultivator, then there has to be some merit in the concept.

Nick Fone

For more up-to-date farming news click here and subscribe now to profi and save.