Faced with extortionate costs to install power to his family’s farm, one Derbyshire farmer and contractor decided to go totally off-grid, adopting roof-mounted solar panels with energy storage using battery packs, in combination with a wood boiler for hot water and heating.

KEEPING IT BRIEF

- 80hp generator tops-up batteries when needed

- Excess solar energy is used for immersion heaters

- Annual panel cleaning maintains performance

When Derbyshire livestock farmer and contractor Neil Green and wife Sarah gained planning permission in 2018 to convert one of their farm buildings into their home, the pair believed that bringing power to the farm through the local utilities supplier would be simple and straightforward.

Not so.

Bringing power up from the nearby village of Tansley, over a distance of around half a mile to reach Oxclose Farm was going to set them back an eye-watering £100,000. An alternative supply route, running across a neighbour’s two fields from an existing pole was thought to be a more favourable solution. That was until the neighbour’s land agent sought to leverage an easement of around £60,000 for the privilege of accessing power.

“The greed involved actually did us a favour,” explains Neil Green. “So we looked at going off-grid, with a system that could successfully power the farm and our home.”

The farm had already invested in a 200ft deep bore hole to supply water for livestock. This supply could be piped to the house and with accompanying UV and particle filters, the Greens could ensure a clean and healthy supply of drinking water was available.

“All we had to do was buy into an electricity scheme that could harvest, store and supply power, which we could use on a year-round basis,” he says.

At Oxclose Farm, Riber near Matlock, Neil along with wife Sarah and son James, usually keep around 80 head of cattle. The farm is looking to grow this enterprise, with a set-up that revolves around 10 pens, with 10 calves per pen.

Stock arrives as calves and are reared to around six to nine months of age when they are moved on to a regular buyer, as stores. While the livestock customer provides a bespoke ration as part of the stock rearing process, Neil Green produces around 150 round bales of haylage each year. While Neil operates his own mowing, tedding and raking equipment to manage dry matter content, a neighbour supplies the baler.

In addition, a flock of pedigree Jacob sheep provides a supply of fat lambs that are sold in boxes, with very little going to waste. “We even sell the skins, as rugs,” adds Neil.

His contracting business has been scaled back in recent years, and Neil continues to include hedgecutting but on a more manageable scale. The lion’s share of the workload is handled by his JCB 3CX backhoe loader, carrying out on-farm ditching, drainage and farm track repair work. Having chased and achieved the dream since starting his business in 1992, he now enjoys a finance-free approach to tractor and machinery ownership, and has recently diversified into firewood supply service along with a good friend, having invested in a Posch a firewood processor.

Running older kit is not without its challenges, and Neil admits that he perhaps spends more time in the farm workshop to ensure he keeps on top of maintenance with his modern classic fleet. Doing so requires a decent supply of electricity to run a collection of workshop kit including compressor and welder, plus a host of essential power tools.

“We looked into a lot of options to give us a reliable and dependable source of power, and settled on a solar panel system that could be installed on the roof of our buildings,” he says. “There’s a lot of roof space, so why not make use of it?”

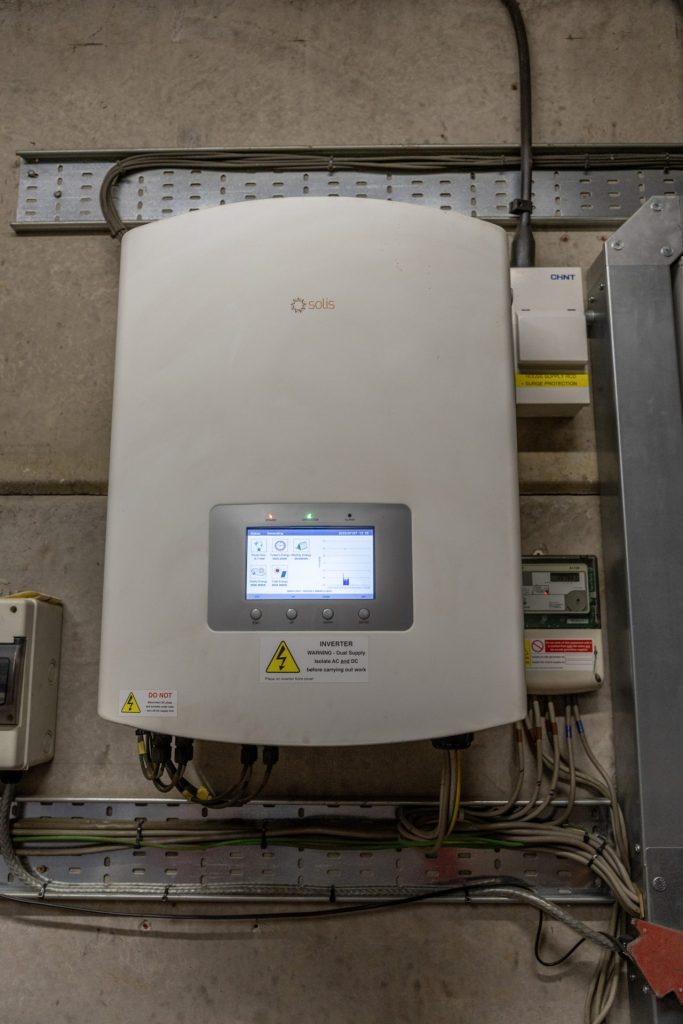

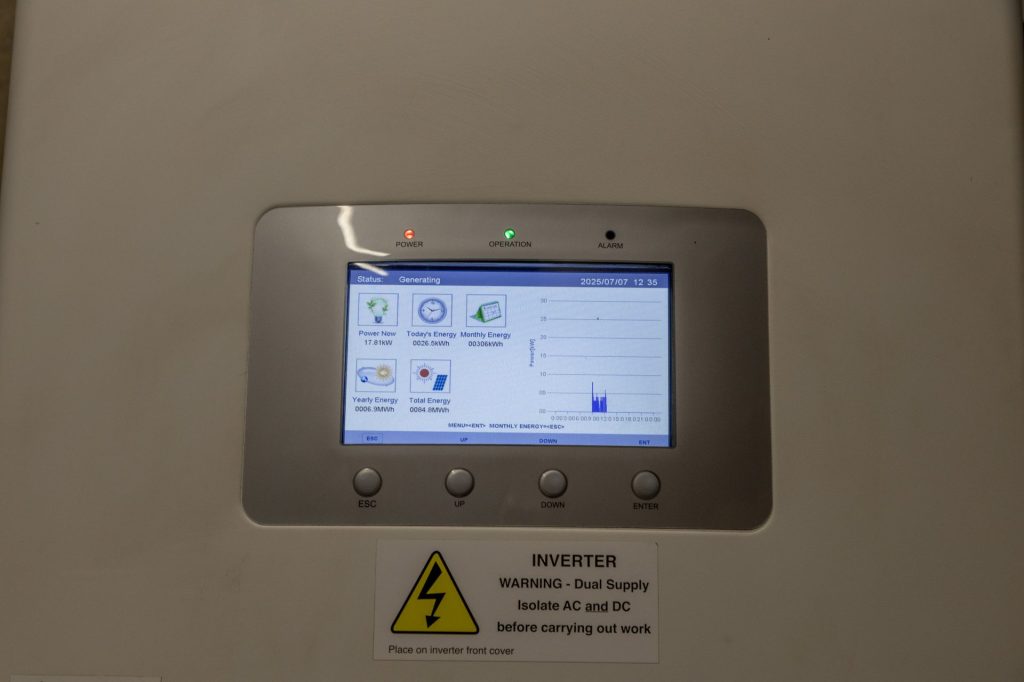

The Green’s off-grid power supply is generated by an array of 77 photo-voltaic panels spread across two roof areas. Collectively, the panels are capable of generating up to 20kW at their peak. This power is collected through a Solis inverter, which feeds the harvested electricity into a BYD battery storage pack comprising eight, 2.56kWh 51.2-volt lithium batteries, offering a total storage capacity of 20.48kWh.

Stored battery power is accessed using three Victron Energy inverters – one for each phase. This enables a 240-volt supply to be used for the house, in addition to a 415v three-phase supply for the farm and its workshop.

“There’s more than enough power available to run my 450-amp MIG welder,” says Neil. “And if I’m welding on a sunny day, the power will come straight off the panels, through the inverters and is not drawn from the batteries. We’ve seen peaks of up to 25kW from the panels, but the average is much less.”

Conscious of energy consumption, Neil says Led lights are used throughout the buildings and workshop, limiting the amount of energy drawn from what’s available in the battery storage.

Living in the Derbyshire Dales though, is not without its off-grid challenges and through the winter months with the shortest days, the solar panel system is unable to keep up with demand. It’s also an area known for snow fall, and the lightest dusting on those roof-top panels is enough to prevent any power from being harvested. Because of this, the farm does have a plan B, which was built-in to the power plan.

“I went up on the roof one winter to clear the snow from the panels, and realised how green and dull they had become,” he says. “They hadn’t been cleaned in their first four years of use, and now it’s part of our annual maintenance. Clean panels mean peak performance so we can harness as much of the sun’s energy as possible.”

“That said, it’s essential that we have a back-up power supply,” adds Neil. “And to get the batteries back up to 100% capacity in winter, we have a 40kVa three-phase diesel generator that makes up for any shortfall.”

He says that the farm cannot get through winter without help from the generator, as consumption from November to February is more than what the solar system can generate.

“We do get bright, crisp winter days that do yield energy from the panels, but it’s not enough to fill the batteries,” he says.

With the entire system accessed through an app, power generation and consumption can be monitored. While the back-up generator can be used automatically to kick-in when battery levels drop to around 15% capacity, Neil prefers to run the generator as-needed during those dark winter days.

“There’s nothing worse than the generator starting in the middle of the night,” he says. “So when we’re in the sheds feeding calves and livestock, and the lights are on, it’s easy enough to run the generator just to top-up the batteries in the day time, so we can get through the night.”

Typically, he says the generator is only used for one to two hours per day from November to the end of February. Over the four months’ use, a few litres of diesel each day is the system’s only annual cost.

As part of the off-grid focus, the farm has installed a gasification boiler for its heat source, burning wood in exchange for warmth. This solid-fuel central heating boiler operates at a high temperature – typically 500 degrees Celsius – using wood with a moisture content of less than 18%.

This boiler heats a 5,000-litre insulated water tank, which is used to supply heat to the farmhouse. It does this through a pair of heat exchanger coils, positioned in the tank. The lower one – and therefore the coolest – is used to run the farmhouse’s underfloor heating system on the ground floor and also its central heating system, which uses conventional radiators throughout the upstairs rooms.

The upper coil is where the tank is at its hottest, is used for hot water to supply the kitchen and bathrooms, operating at around 65°C.

“Having 5,000 litres of water in an insulated vessel creates a great thermal mass, so once it’s warmed through, it doesn’t take much topping up,” says Neil. “And we do use a lot of hot water for mixing up milk powder when calf rearing.”

“The underfloor heating system is capable of blending hot and cold water, so the water temperature circulating through the underfloor pipework is cooler than that in the radiators, and is maintained at a constant 37°C.”

Though Neil says that a drop in the floor temperature is the first alarm bell that indicates the wood boiler needs to be relit.

“I only light the wood boiler every three days in winter, but this increases to every other day when it’s really cold,” he says. “Each fill requires a wheel barrow of logs, and the amount of ash in the bottom after a burn is minimal. I’d like a larger boiler, so it can burn for longer and therefore doesn’t need lighting as frequently.”

In addition, the 5,000-litre water tank also carries three immersion heaters, with any excess power from the solar panels being used to heat the water tank, once the battery storage is full.

“In the height of summer, those eight batteries are usually at full capacity by 10am, and we’re still producing electricity,” he says. “Running immersion heaters is the best way to absorb this excess electricity and it means we don’t need to light the boiler through the summer, simply because the panels are producing more than we can use for everyday tasks.”

We do have some servicing costs for the entire system, but they are marginal,” he adds. “For example, oils and filters for the generator’s Perkins Phaser engine, plus UV and particle filters for the water system, and our other cost is that of logs, for the wood-fired boiler.”

But with a plentiful supply of wood, and diversification into firewood processing, the availability of logs is low cost.

“We burn the equivalent of a 12-tonne grain trailer of logs every year,” he says. “It’s not an expensive system to run for what we get out of it, in fact, it’s a very cost-effective way of securing an electricity supply, a water supply and a source of heat for our family farm.”

Six years in, Neil reckons the system is working well, and is perhaps as low-cost as it gets.

“We don’t get any utility bills, which is brilliant,” he says. “And the cost of the system has worked out at about £60,000, which included electricity and heating, plus plumbing for the farmhouse.”

His next move could be to add a small wind turbine to supplement the existing system, adding that a wind turbine capable of producing five or six kW would bring an element of additional security to power generation at Oxclose Farm.

“It would be useful to keep collecting some power when the weather means the panels are barely getting by,” he says. “Fog, cloud cover and dark days are the worst offenders, and even very heavy rain can have an impact on what the panels produce.”

“It doesn’t help that our buildings are adjacent to a woodland, either,” he adds. “There’s an element of shading when the sun is low, which is a compromise for us when using existing buildings. So a small turbine would keep spinning when the wind blows – and there’s no shortage of that around these hills.”

Neil says that if he was starting again, the chances are he’d follow the same path, but would erect another building in a different location on the farm where there’s greater visibility to the sun.

“Panel angle is very important, but when we were starting this journey, cost was a key driver, and so we worked with the buildings that were already in place,” he says. “It would be good to use a heat exchanger on the generator too. But overall, we’re very happy with the energy independence we’ve got.”

Summary

While Neil and Sarah Green’s decision to go entirely off-grid wasn’t the family’s first choice for acquiring on-farm power, the prospect of being held to ransom for what is deemed an essential utility brought out the very best in lateral thinking from this cost-conscious contractor. It’s a lesson to all, that traditional and established processes along with reliance on others, is not always for the good of your own bank balance, or your sanity.

Geoff Ashcroft

For more up-to-date farming news click here and subscribe now to profi and save.